Press Release

As the third installment of our series RELAY, Leo Koenig Inc is delighted to present:

Mahogany, Oak, and Pine:

works by LeCorbusier | Charlotte Perriand | Sherrie Levine

Traditionally, different types of trees and the material they embody have powerful meanings beyond their names and categories. Symbolically, Mahogany imparts sturdiness and protection, while Oak denotes wisdom and resistance and Pine signifies both longevity and humility. Hardness can be advantageous or troublesome, dependent upon the application. Once a living thing, the material is eminently changeable with exposure to climate, pressure, and manipulation yet remains singularly recognizable.

At first glance, the works in Mahogany, Oak, and Pine find connection through materiality, but intersect and diverge in surprising ways. Identifying characteristics are either ardently highlighted or clinically annulled. Notions such as degrees of strength and resilience, scarcity versus abundance, and the precious in opposition to the everyday all announce themselves much like striations of the grain.

Le Corbusier always tempered his modernist designs with the warmth of wood. When speaking of his early mentor Charles L’Eplattenier, he wrote that L’Eplattenier had made him “a man of the woods” and taught him painting from nature. With his generous incorporation of the technique Breton Brut, (a type of casting concrete that leaves the impression of the cast material on the surface) Le Corbusier carried the impression of the wood grain through to the cool dispassion of concrete, while ever contrasting the two materials.

For his collaborator, Charlotte Perriand, wood was a preferred medium. Though she was quoted as saying “I like the precision of metal, its gloss, and color when it’s lacquered,” she added, “I like caressing wood.” Once meticulously sanded and rubbed by hand, even the knottiest timber, as the designer memorably put it, could be rendered “as soft as a woman’s thighs.” Interestingly, many of the elements for the dormitory rooms were first proposed in steel but were soon deemed unaffordable at the time. At the height of Le Corbusier’s and Perriand’s careers, wood was both plentiful and affordable, which was an important precept in their insistence of bringing good design to a wider audience and their belief of improving society with the implementation of design. The utilization of wood in the dormitory rooms from Maison du Brésil exemplifies these precepts while relying on the timber to perhaps provide a keynote that resonated with the native culture of the students it would house.

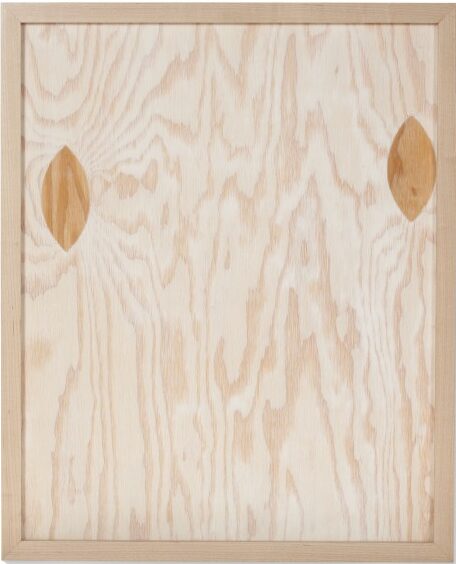

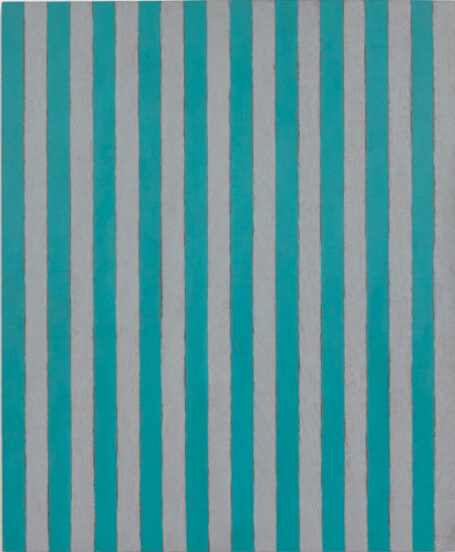

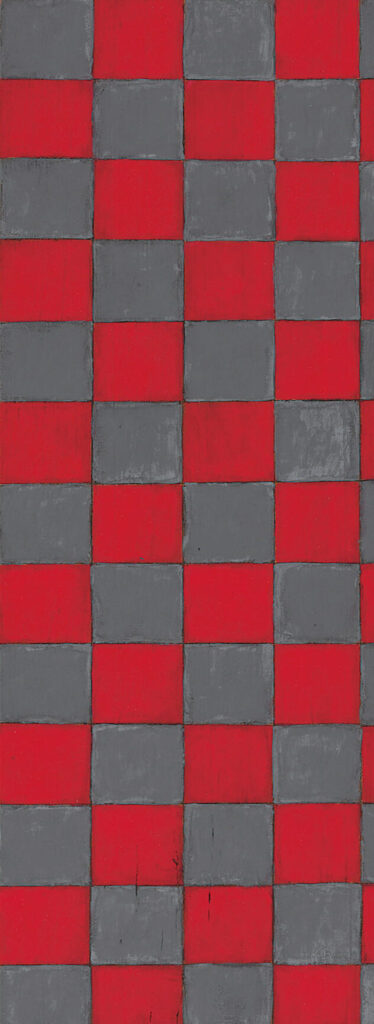

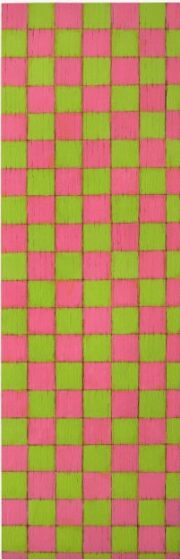

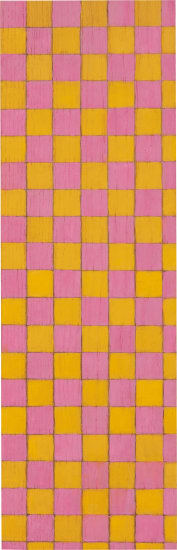

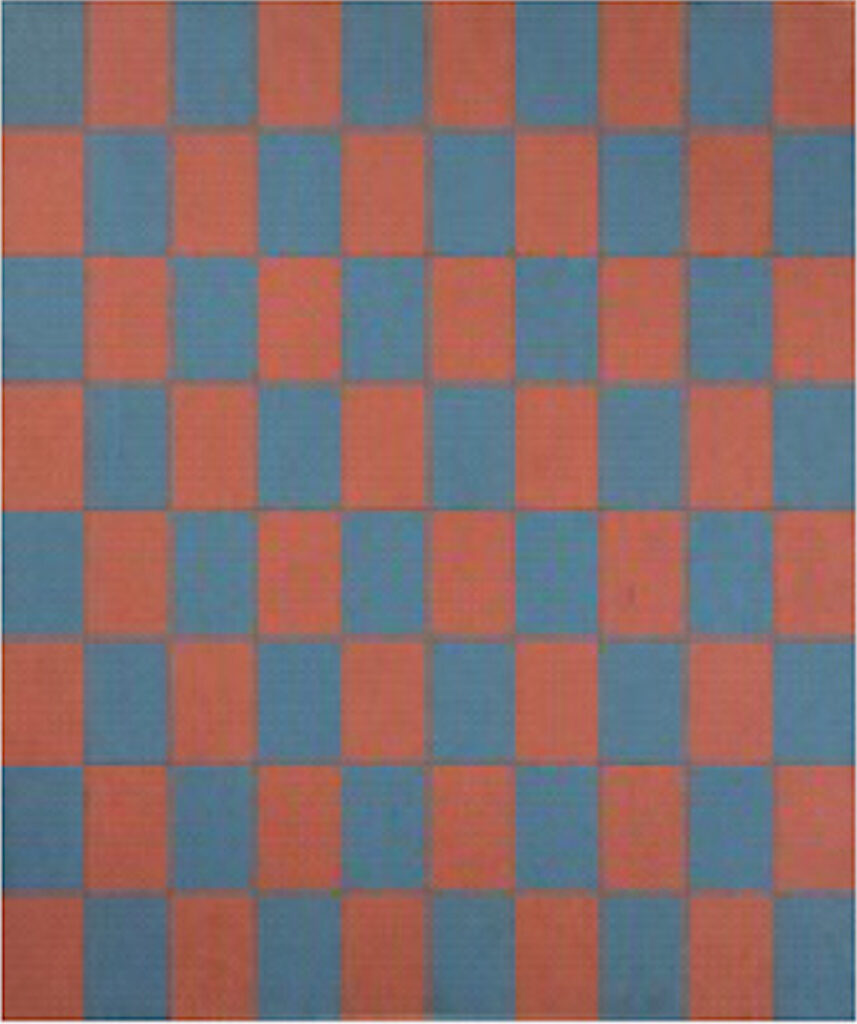

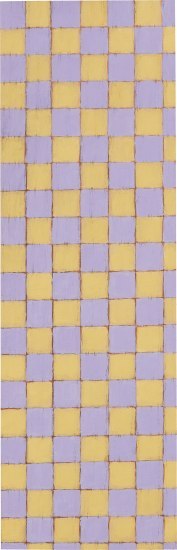

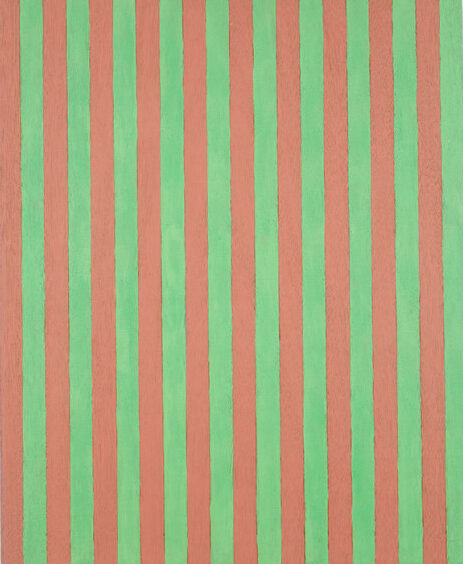

In Sherrie Levine’s “Knot Paintings”, the pun of “Not Painting” obviously brings attention to itself. In these works, Levine uses plywood, a cheap and mass-produced type of wood glued together out of rejected, discarded layers, and typically used to make crates to house paintings. Levine paints out or highlights knots in the woodgrain, confusing a fundamental characteristic that typically defines, making a point of its absence. In her check and striped paintings, Levine refers not only to the Minimalist grid but, the Surrealists’ emphasis on chance and play. Her choice here was to paint on mahogany, a wood that is known for its rarity and preciousness, challenging that hierarchy and further illustrating her “head-on confrontation with the anxiety of influence”.

Le Corbusier (Swiss, 1887–1965) was the pseudonym for Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, a pioneer of modern architecture, a painter, and a theorist. Le Corbusier attended the La-Chaux-de-Fonds Art School and studied under architect René Chapallaz,

In 1907, the artist went to Paris to work for Auguste Perret, an architect who pioneered the use of reinforced concrete and studied architecture with Josef Hoffman. From 1914 to 1915, he developed Domino House, an architectural model with an open floor plan, columns, and thin walls of reinforced concrete. The theories embodied in Domino House influenced Le Corbusier’s projects for the next decade. n 1918, he and Amédée Osenfant established a new art movement called Purism. In 1922, Le Corbusier presented an urban design plan called Immeubles Villas. Immeubles Villas, and later his Ville Contemporaine, reflected his belief that modern architectural planning could raise the quality of life for city inhabitants.

Le Corbusier, along with Ludwig Miles Van der Rohe and Walther Gropius was considered to be a pioneer of the International style. In 1935, Le Corbusier published a book on urbanism called The Radiant City. After World War II, Le Corbusier used these ideas to create housing blocks around France, such as the Unité d’Habitation of Marseilles. He also designed the first planned city in India, Chandigarh.

Charlotte Perriand (French 1903-1999) studied at the École de l’Union Centrale des Arts Décoratifs. Two years after completing her studies (1925), she began working as an interior designer. Her research and interest in furniture design led her to collaborate with Le Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret in the 1920s and 1930s. During this time, she worked on major projects including the Villa Church, the Villa Savoye, the Cité du Réfuge for the French Salvation Army, and the Pavillon Suisse at the Cité Universitaire.

In 1940, Perriand was appointed as the official advisor on industrial design to the Japanese government and left for Tokyo, returning to France in 1946. All her work thereafter would display a Japanese influence. Major projects followed, notably for Air France (1957-1963) and the Musée National d’Art Moderne in Paris (1963-1965). Perriand’s work has been the subject of many exhibitions, highlighting her “synthesis of the arts” and her singular vision.

Born in 1947 in Hazleton, Pennsylvania, Sherrie Levine studied at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, where she received her M.F.A. in 1973. In 2011, the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York presented MAYHEM, a major exhibition of Levine’s work spanning three decades. The show included one of her most acclaimed series from 1981—After Walker Evans: 1-22. Referencing the loss of uniqueness as a result of mechanical (and digital) reproduction and ironically using a medium generally held responsible for diminishing the value of the artist’s hand, the work was a description of the pictures in contextual, rather than formal, terms.

Levine’s work has been the subject of solo exhibitions at prominent institutions worldwide, including at Neues Museum, State Museum for Art and Design in Nuremberg (2016); Portland Art Museum, Oregon (2013); Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany (2010); San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (2009 and 1991); and the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, New Mexico (2007). Other venues include Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen, Germany (1998); Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; The Menil Collection, Houston (both 1995); Portikus, Frankfurt (1994); Philadelphia Museum of Art (1993); Kunsthalle Zürich (1991); High Museum of Art, Atlanta; Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC (both 1988); and the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut (1987).

Major group exhibitions include Brand New: Art and Commodity in the 1980s, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, DC (2018); Ordinary Pictures, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, Minnesota (2016); America Is Hard To See, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York (2015); Prima Materia, Punta della Dogana, François Pinault Foundation, Venice (2013); The Pictures Generation, 1974–1984, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (2009); Whitney Biennial (2008, 1989, and 1985); SITE Santa Fe (2004); São Paulo Biennial (1998); Carnegie International (1988); and documenta VII (1982)

Gallery hours are Tuesday through Fridays 11-6 except for the month of AUGUST when we will be open by appointment only. For more information, please call 212.334.7855 or email us at info@leokoenig.com.