Press Release

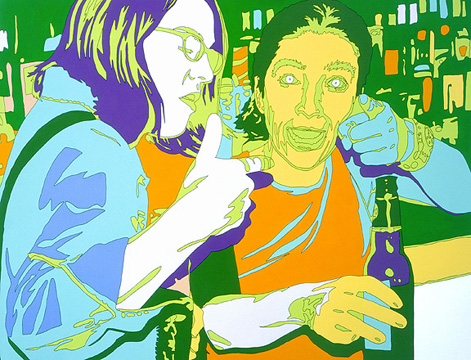

Lisa Ruyter’s new works are party paintings. Made from photographs taken late at night in restaurants and bars, Ruyter’s new pictures are still in vibrant color, however, they are more Weegee than Warhol, for they resemble nothing short of crime scenes. These new paintings reveal much about what Ruyter has been looking at intently, namely American straight image photography and the work of driven paparazzi. Almost unnoticed, she has been moving through the art world over the past year taking relatively unflattering photographs of what she’s now rendered as a demimonde. Her new pictures might best be read against such social landscape photographers as Robert Frank, Garry Winogrand or Lee Friedlander, or against the recent event pictures of Jessica Craig-Martin.

The color in Ruyter’s new work seems more akin to the photomontages of Gilbert and George than to anything seen in contemporary painting. Like the forced colorization of old black and white films, Ruyter’s colors refuse to hold on to flesh ‹ to flesh out reality; to imbue skin with the color of life. Instead her imposed colors are brutal, deathly; an aggressive act carried out against the original image. Like the narratives which we frequently spin around our ever waning memories, Ruyter’s grafted-on colors re-cast her camera originals. It is the distance between the color as photographed (as it really was) and the color as painted, which creates an interpretive space for the viewer. Ruyter is no longer using color to create a set of harmonics but rather to force a dissonance through which her intentionality and our reading can perpetually vie one with the other.

Ruyter’s recent work expands her ever-widening autobiographical project ‹ a project through which she has shared her life with a growing audience. From paintings of listless suburbia, to travelogues of Europe and the Americas, Ruyter has shared her family; her interest in popular music; in the cinema; in travel and in sports. She has also recently completed a number of large-scale projects and cycles of paintings that deal with the complex binary of death and the thirst for immortality. In this new body of work, Ruyter shares her friends, and the artists and staff of her New York gallery. Quite simply, Ruyter continues to paint the world in which she finds herself, and she does so with great generosity.

In these new frozen tableaux of revelry, the figures are frequently outlined not with colored glows of aura but, rather, with psychedelic effects caused by the camera’s flash in the originary photograph. Ruyter thereby doubly emphasizes the corporeality of her subjects while flattening her renderings. These figures, as they are, mediate the distance between sleepwalking and consciousness. This ambivalence, this perpetual fluctuation, appears now to have been the central characteristic of her work all along. Her celebratory paintings of graveyards have made this ambivalence clear. That we haven’t noticed this before is either a testament to her craftiness or proof positive of our blind spots.