Press Release

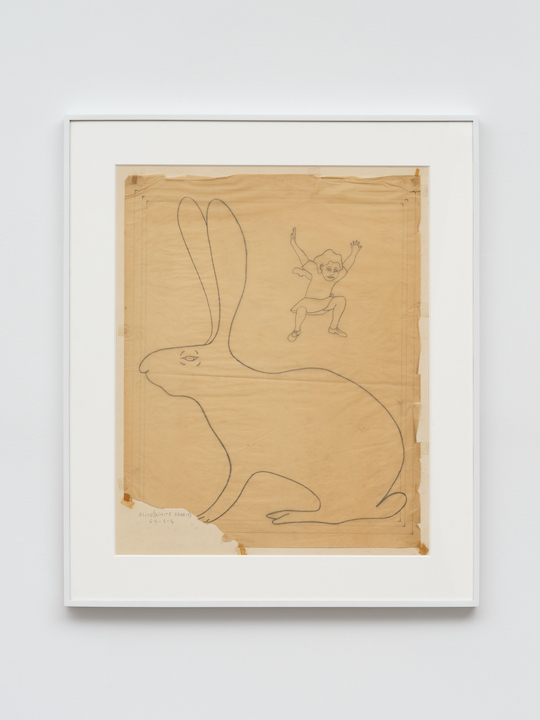

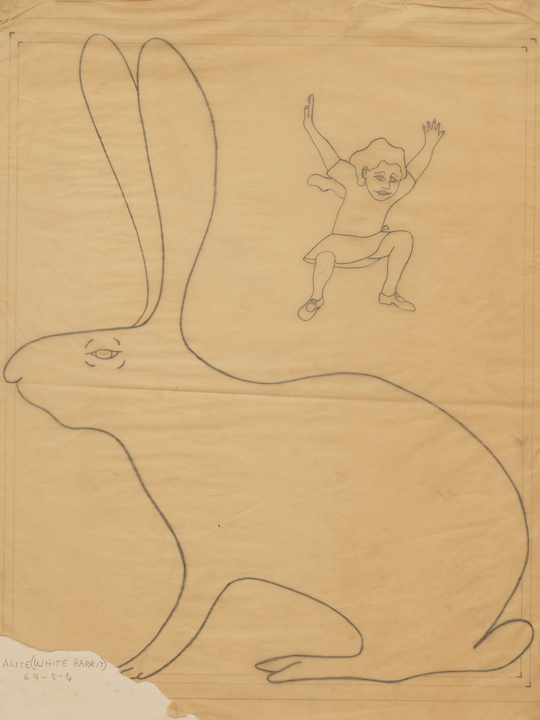

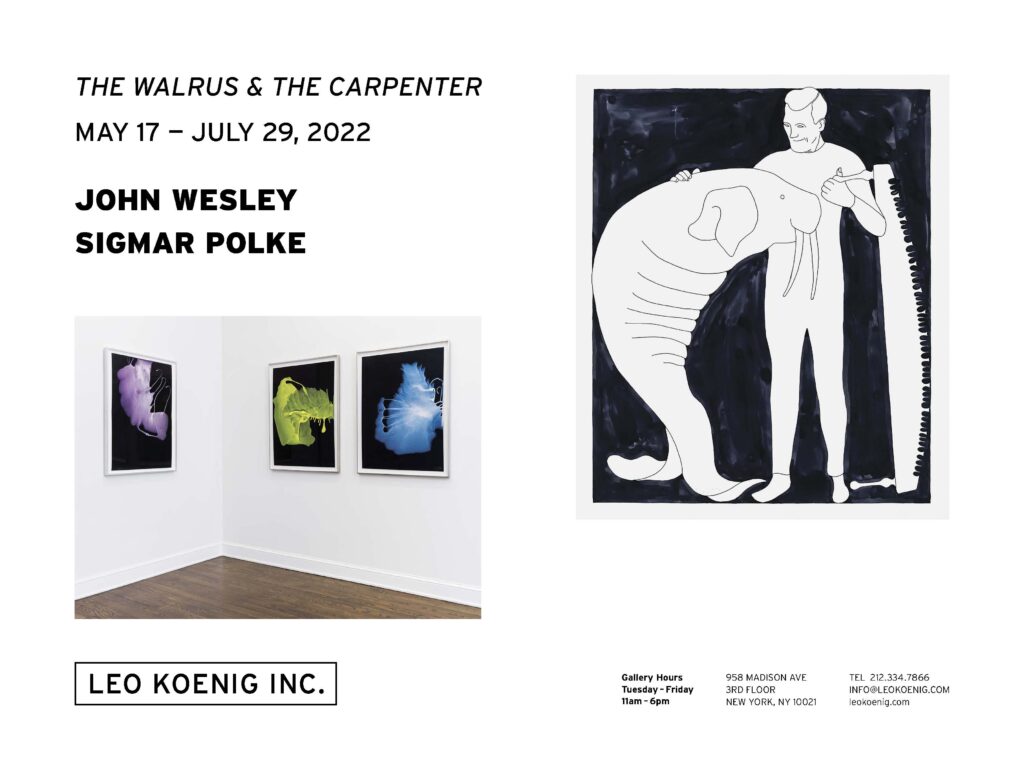

Leo Koenig Inc. is delighted to announce the opening of The Walrus and the Carpenter. Taken from the title of one of John Wesley’s paintings, the title seemed to present a perfect jumping off point into the sublimely absurd elements in the two artists’ works.

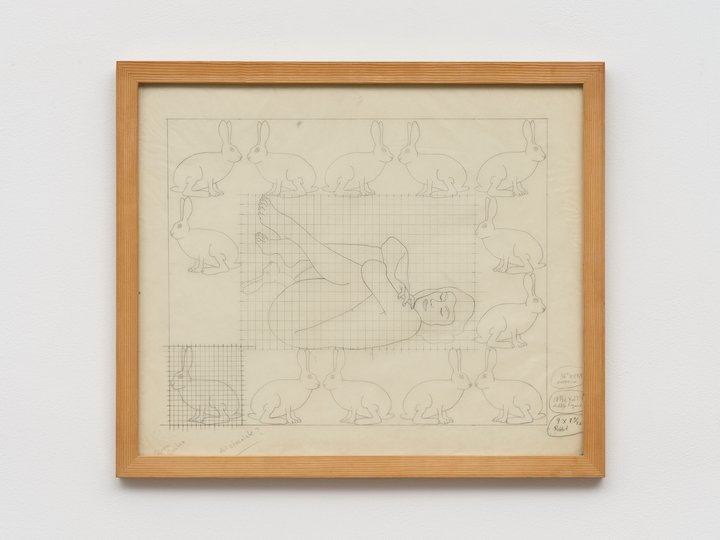

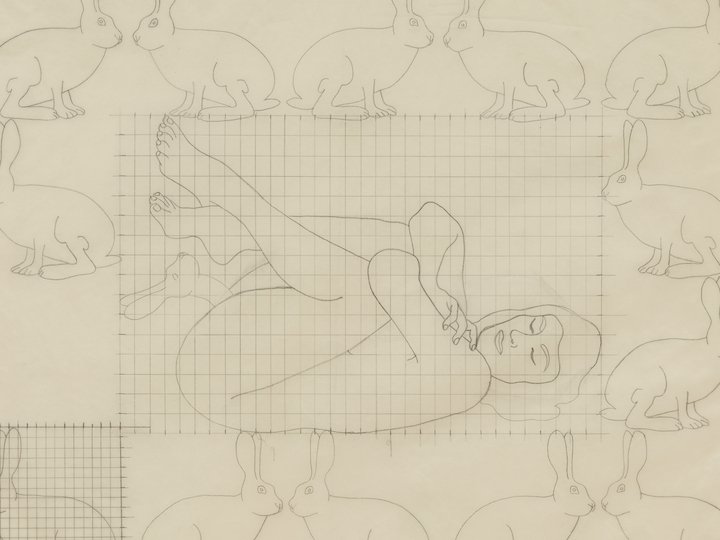

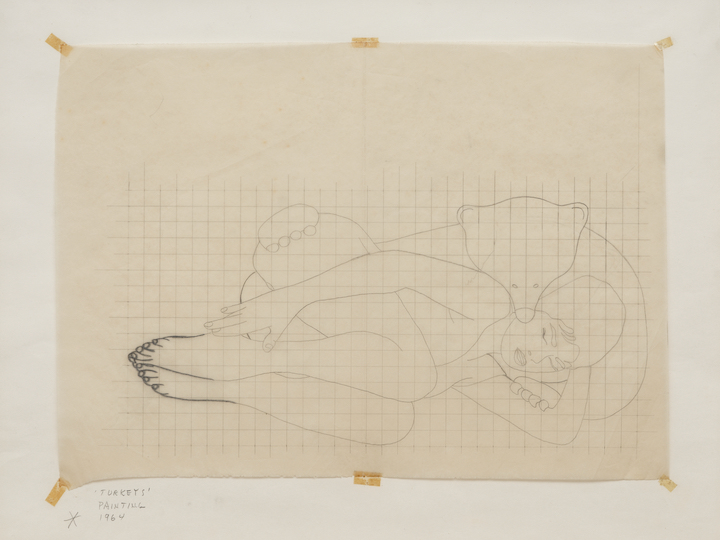

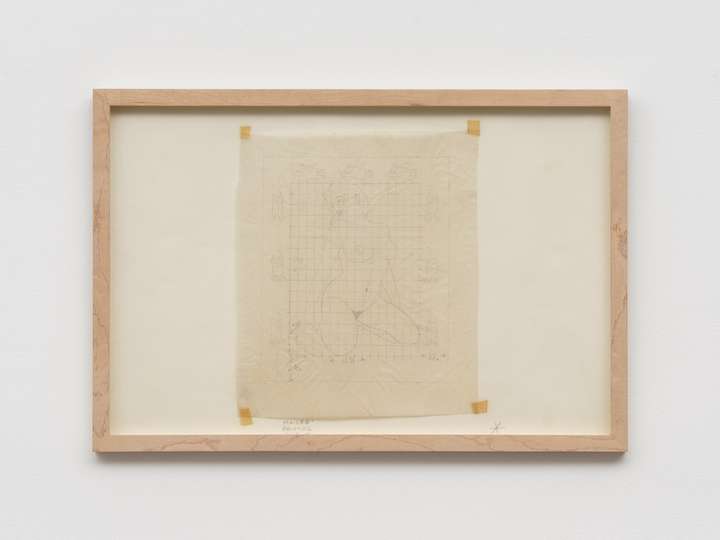

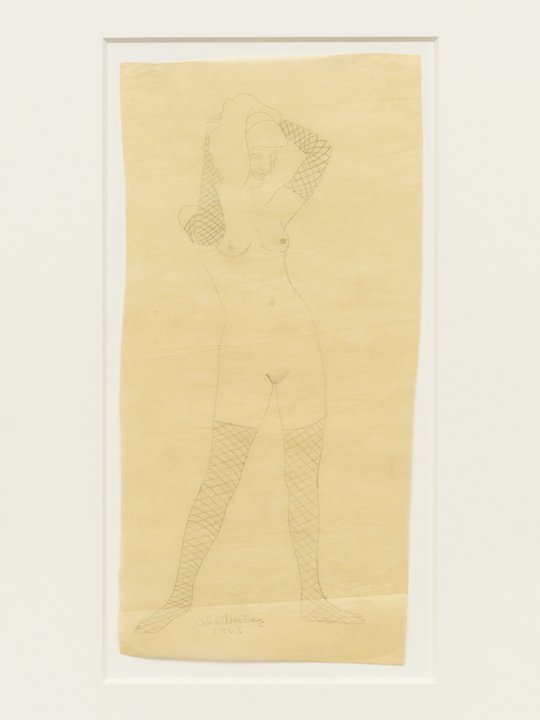

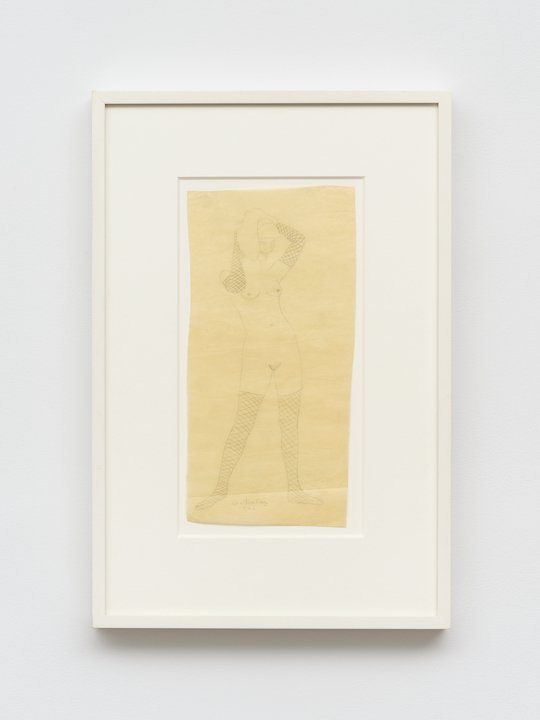

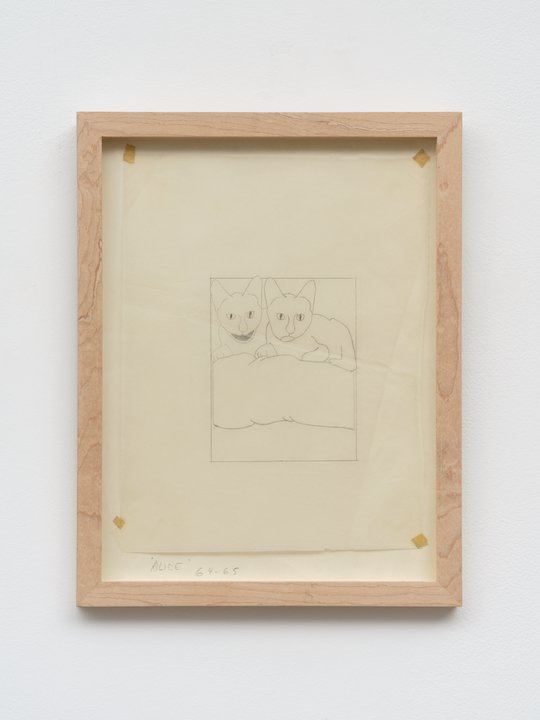

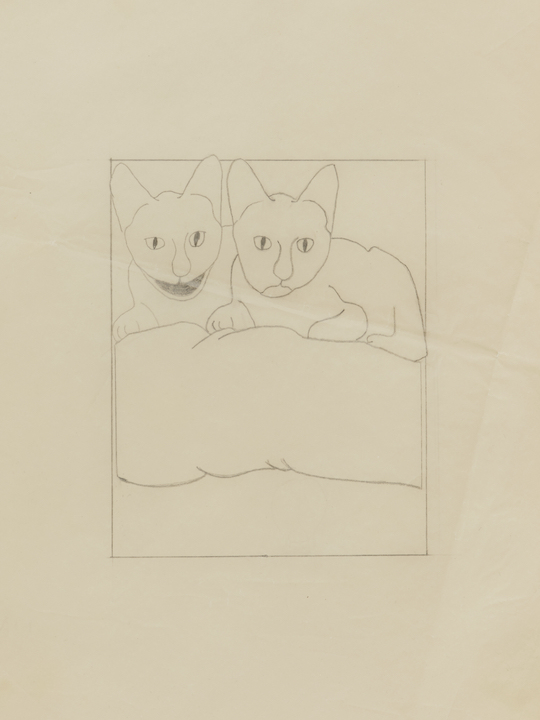

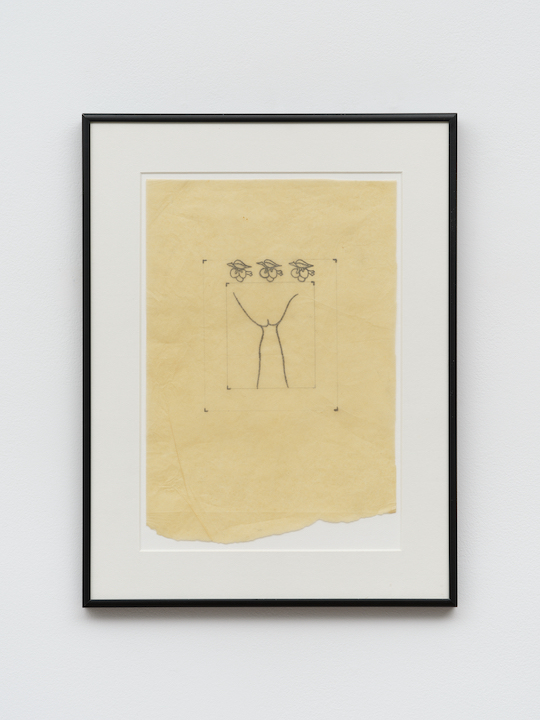

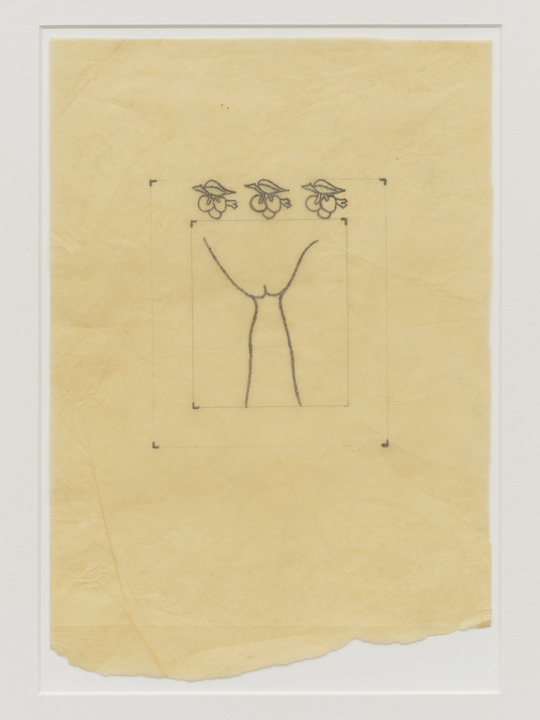

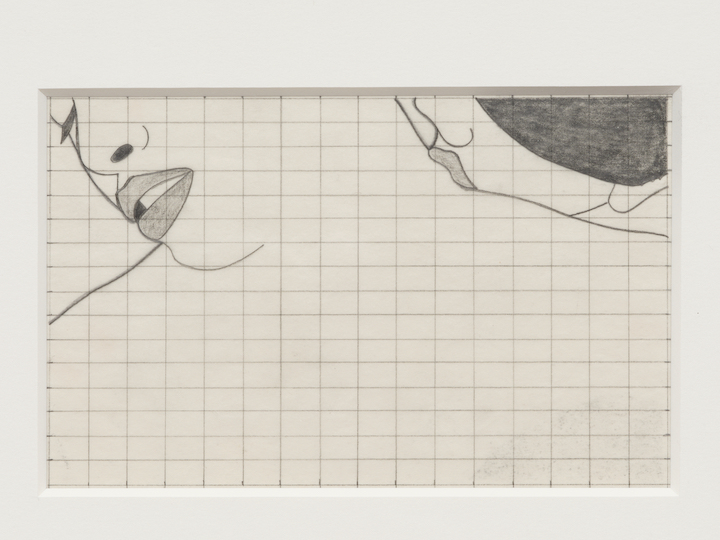

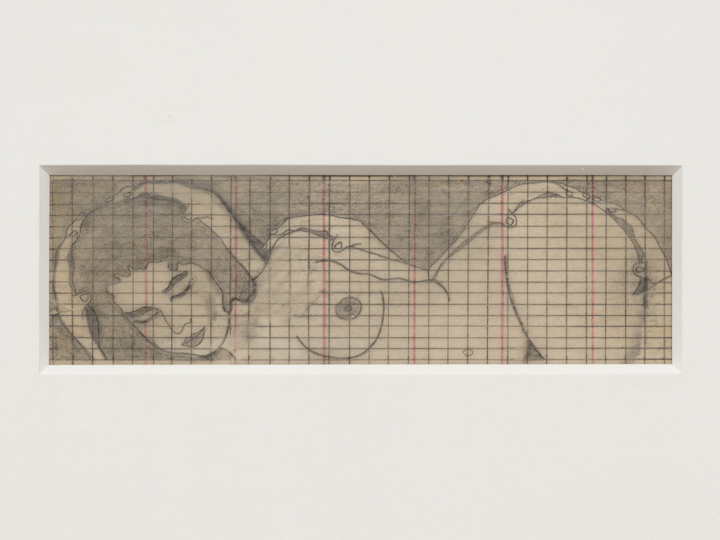

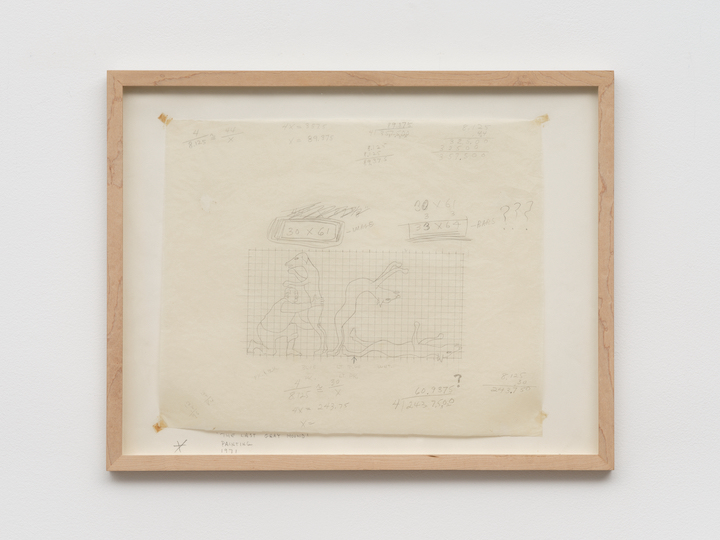

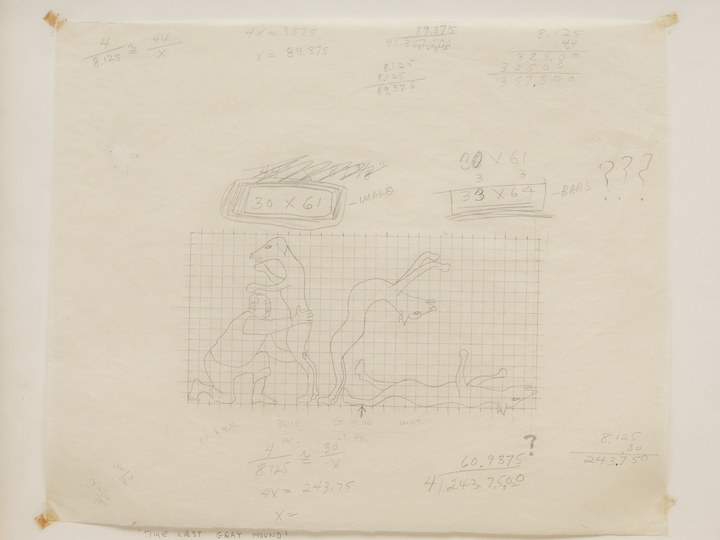

Referencing a Lewis Carrol poem that is recited by Tweedledum and Tweedledee to Alice in Through the Looking Glass, The Walrus and the Carpenter touches on themes of death andbetrayal and to a certain cunningness in human nature. But it does so in such a comic fashion, that the point is nearly overlooked. Likewise, in John Wesley’s paintings. We see a graphic style, repetition, (which for Wesley accentuated humor), beautiful maidens, animals as characters and famous figures as George Washington’s head appearing as pattern anddecoration. In a Journal celebrating Johns Wesley’s work printed in 1974 “The Unmuzzled Ox,” the artists wife Hannah Green wrote this: “Jack never does anything obvious. His ideas come as the mind turns (like the globe) into darkness. His mysterious and varied iconography must have a certain magic, a certain mystery for himself as well. Thus his work has the power of true surrealism. His humor is original, unique to John Wesley. Thus the enigma entwined like a riddle in each painting is the result of his psychic method.” Indeed the artist felt more akin to his work being surrealist in nature than Pop. Wesley’s work is random, yet deliberate, as we journey through a world that is at once humorous, absurd and unnervingly poignant

In contrast, Polke’s images tend to blur the lines of painting, photography; documentation andstaging, hallucination and reality. With this in mind, where these two artists converge is at a sideways entry into a peculiar surrealism. Through different modes, each artist explores an altered reality. Whereas Wesley’s precision creates a world of hallucinatory juxtaposition, for Polke, his materials are an impetus. Arsenic, meteorite dust, snail slime, coffee and soap were all in his repertoire of experimentation. It seemed, as an artist, he continuously asked morefrom his materials. There exists within his oeuvre, the nascent idea of materials that are participatory in the act of creation, much as an invisible hand that guides the resulting image taking shape. For his Uranium series, Polke placed radioactive uranium on photographic plates to produce the aura-like images. In the Interference works; paints made with mica and other light altering materials are allowed to move along treated paper. In the painting Untitled, 1990, we acknowledge an exuberance fighting the containment of the window of thecanvas. Here again the materials help plot out the scene, abstracted yet familiar, guided, but self-determining.

*Leo Koenig Inc. would like to thank Fredericks and Freiser Gallery for their generous assistance with this exhibition.

John Wesley has created an ineffable body of work whose subject is no less than the American psyche. While many artists of his generation have used the popular image to explore thecultural landscape, Wesley has employed a comic-strip style and a compositional rigor to make deeply personal, often mysterious paintings that strike at the core of our most primal fears, joys, and desires.

Originally grouped with the Pop Art movement, and later on linked, due to the essentiality of his production, to Minimal Art (to such an extent that Donald Judd and Dan Flavin were counted among his greatest admirers), Wesley eludes simple classification. In fact, Wesley himself found both terms (Pop and Minimalism) to be reductive. Wesley keeps a great distance from the aggressive reality of Pop and the unambiguous materiality of minimalism in favor of turning inward toward a radical intimacy.

John Wesley has been exhibited and collected by museums worldwide since the 1960s. Surveys of his work have been held at the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, curated by Rudi Fuchs and Kasper Koenig (travelled to Portikus); Museum Ludwigsburg, curated by Udo Kittleman (travelled to DAAD, Berlin); PS1 MoMA, Long Island City, curated by Alana Heiss; Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, MA, curated by Linda Norden; Museum Haus Lange, Krefeld, Germany, curated by Martin Henschel; Chinati Foundation, Marfa, TX, curated by Marianne Stockebrand; and Fondazione Prada at the Venice Biennale curated by Germano Celant. Since 2004, the Chinati Foundation, Marfa, TX. has maintained a permanent gallery housing its collection of Wesley’s paintings, as was intended by Judd since the foundation’s inception. In 2014, Wesley was commissioned to create a public art project for the High Line. The artist has had over 70 solo exhibitions including 14 at Fredericks & Freiser.

Sigmar Polke (Oels Germany (now Poland) , 1941-2010) is considered as one of the most influential artists of the postwar era. Employing an experimental approach to a wide variety of styles, media, and subject matter, Polke used unconventional and diverse materials andtechniques, melded with ironic or humorous imagery, as strategies of social, political, andaesthetic critique.

Starting in 1959, as a glass painter, Polke later enrolled at the Staatliche Kunstakademie Düsseldorf to study painting. In 1963, he, along with fellow students Manfred Kuttner, Konrad Lueg, and Gerhard Richter, organized an exhibition of their own work helping to launch the artists’ early careers andintroducing the term “Capitalist Realism.”

Polke has been the subject of numerous solo exhibitions at institutions, such as the Kunsthalle Tübingen, Städtische Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, and the Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, Eindhoven in 1976. In 1983, Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, Rotterdam hosted Sigmar Polke that traveled to Kunstmuseum Bonn in 1984. In 1984. He had a retrospective at the Kunsthaus Zürich and the Josef-Haubrich-Kunsthalle, Cologne. In 1988, Polke exhibited at the Musée d’art moderne de la Ville de Paris. Sigmar Polke. Die drei Lügen der Malerei, was presented at theKunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, in 1997, and traveled to the Nationalgalerie im Hamburger Bahnhof, Museum für Gegenwart, Berlin in 1997-1998. Retrospectives in the U.S included the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago; and the Brooklyn Museum, New York in 1990-1992. MOCA, Los Angeles organized an exhibition of Polke’s photographs (Sigmar Polke: Photoworks. When Pictures Vanish) in 1995-1997, traveling to Site Santa Fe, New Mexico (1996), and the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC (1996-1997). MOMA, New York, organized an overview of theartist’s works on paper in 1999, which traveled to the Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg.

Sigmar Polke was included in numerous international biennales, including Documenta, theBienal de São Paulo, and the Venice Biennale, receiving awards, including the Golden Lion at the West German Pavilion in 1986 at the Venice Biennale, the Erasmus Prize (1994), theCarnegie Prize (1995), the Praemium Imperiale (2002), and the Roswitha Haftmann-Preis (2010). Polke’s work is included in the permanent collections of major museums around the world

The Gallery is open Tues-Friday 11-6. Please observe whatever protocols are in place for NYC when visiting. For more information, please call 212.334.7866 or email us at info@leokoenig.com